Refining Your Style

You should now have a good overview of the tools available to you in Premiere Pro and the Lumetri Color panel. Before we wrap up the color grading section of the course, there are a few final techniques I want to touch on.

Mask Tracking

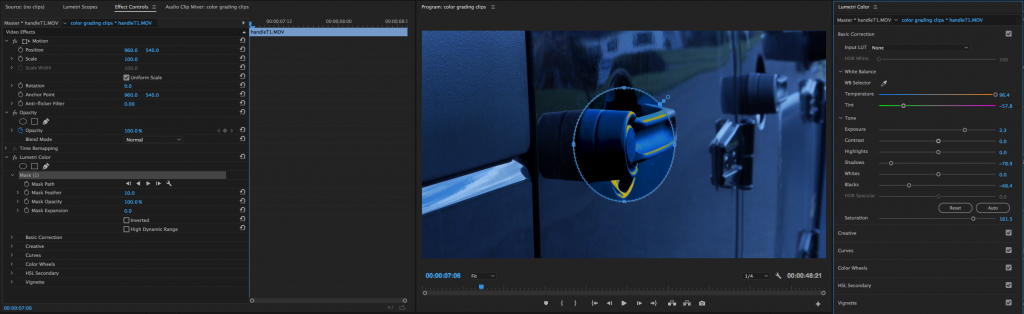

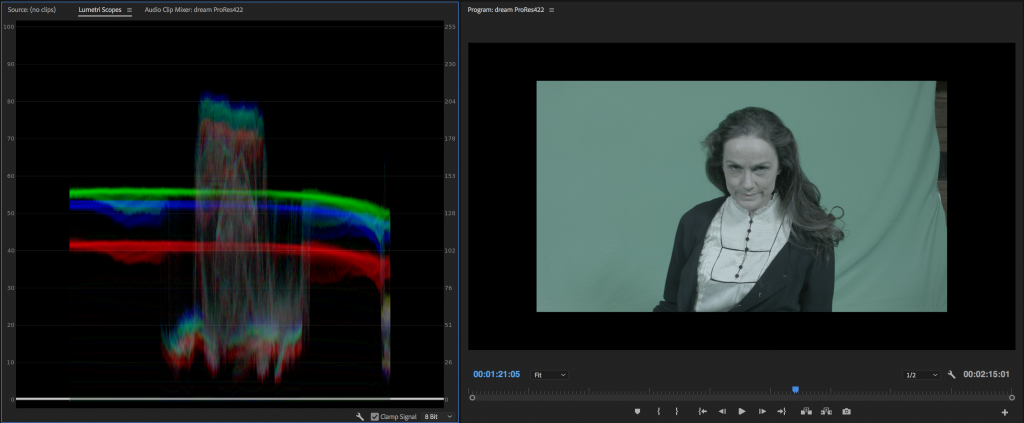

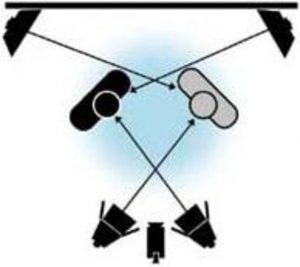

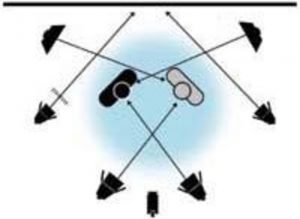

In an earlier lesson, I mentioned the masking tools that are available for Lumetri in the Effect Controls. You have access to a four-point mask, circular mask, and a pen tool that can be used to create a custom shape. These tools are helpful for when you want to correct or grade a specific part of the image, such as the sky. However, they only work well on static shots – unless you use a tracking mask.

Tracking masks follow a specific part of the image. If you wanted to add a specific color correction to an actor’s face, for example, you could draw a circular mask around their face and have the track mask follow it through the shot. Premiere makes this process easier by automatically tracking things in the frame as they move around.

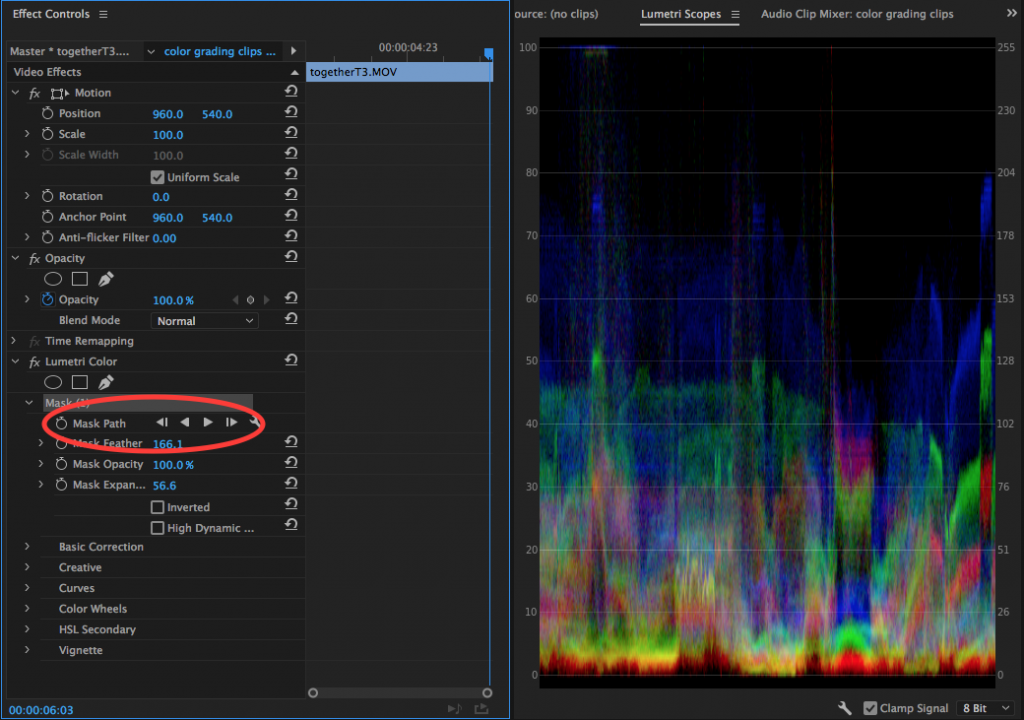

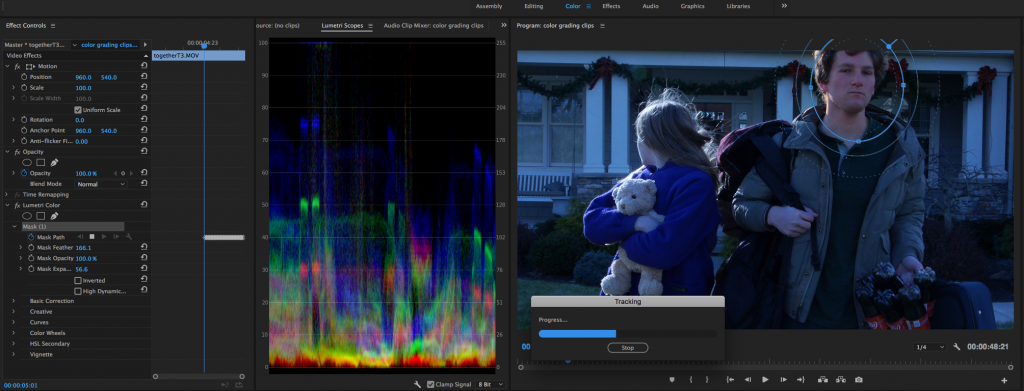

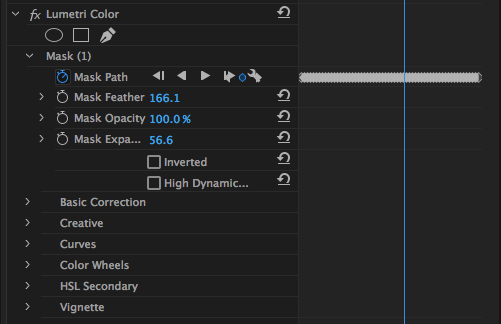

After you create a mask, you should see Mask Path options above the controls for feather and opacity in the Effect Controls. There are icons for frame back, reverse play, forward play, and frame forward, plus a wrench icon for customizing settings: these are the tracking tools. You can leave the wrench icon alone – the default tracking values should be fine. If you click on the forward or reverse play icons, the program will automatically begin to track the footage forward or backward. If you are at the end of the clip, hit the track backward icon; and if you are at the beginning, hit track forward. If you create your mask in the middle of the clip, you will probably need to click one first, then the other.

Hitting either play icon will cause Premiere to scan through the selected clip and create keyframes affecting the movement of the mask. Since it creates a new keyframe for every frame of the clip, this is often a slow process – and one that can be taxing on your computer. I’d recommend using mask tracking primarily on shorter clips without wildly changing movement. With these caveats aside, the automatic mask tracking really does do quite an impressive job of holding on to the area of the image you select with the mask. If the results aren’t quite what you wanted, you can always manipulate the keyframes by manually moving the mask.

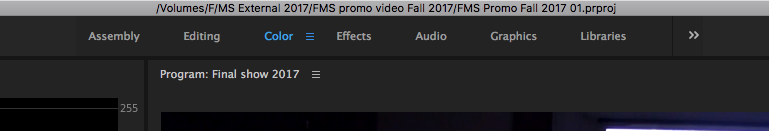

Master Corrections

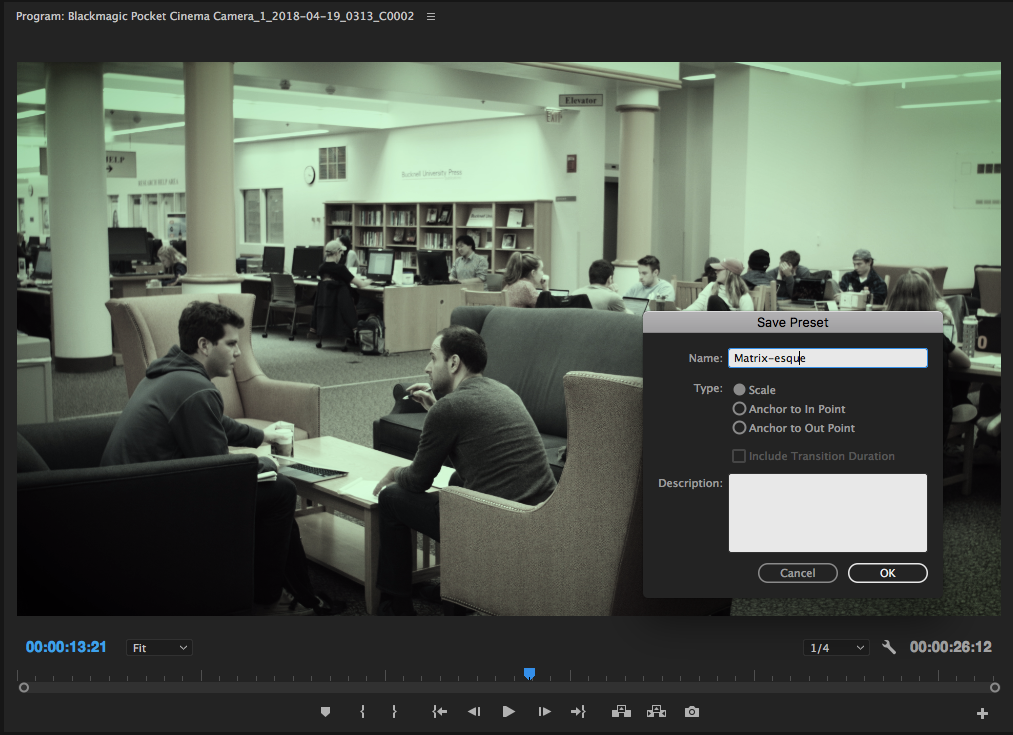

Most of the time, Lumetri is used to color grade shots in the timeline individually. If you want to affect multiple clips, you can either copy and paste the effect, create a preset or LUT, or use an adjustment layer. However, you also have the ability to affect a piece of footage every time it is used in your project. For example, if you have a long take that you use several clips of, you can make one adjustment to affect all of the clips. This is called a master adjustment.

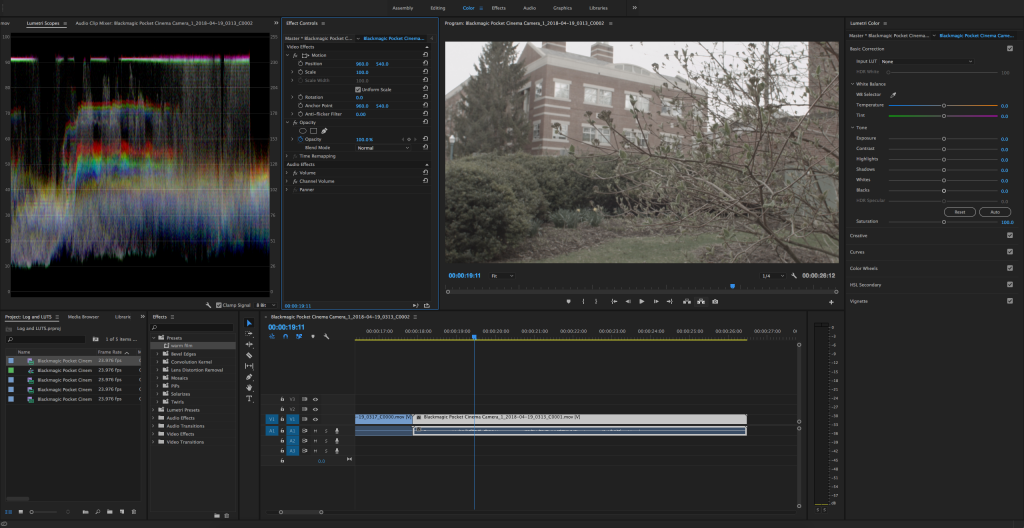

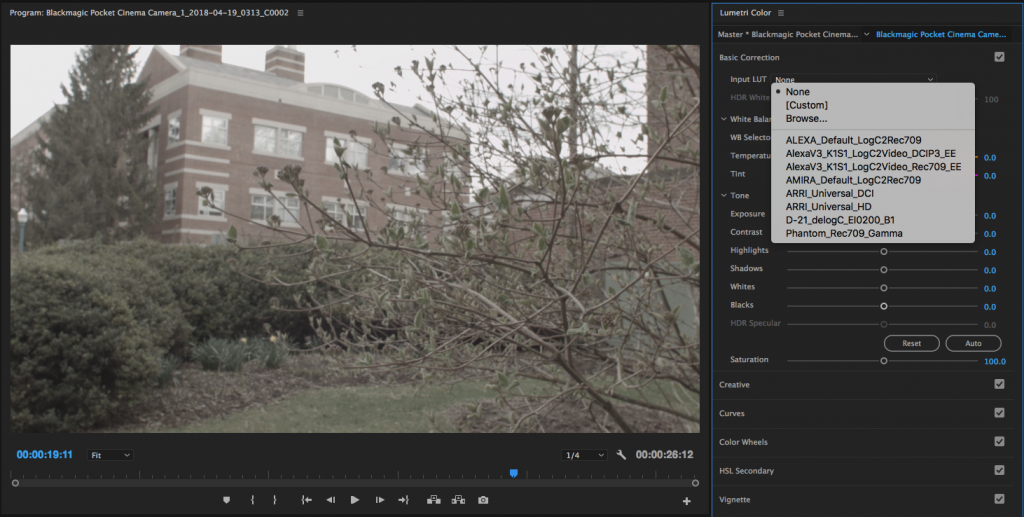

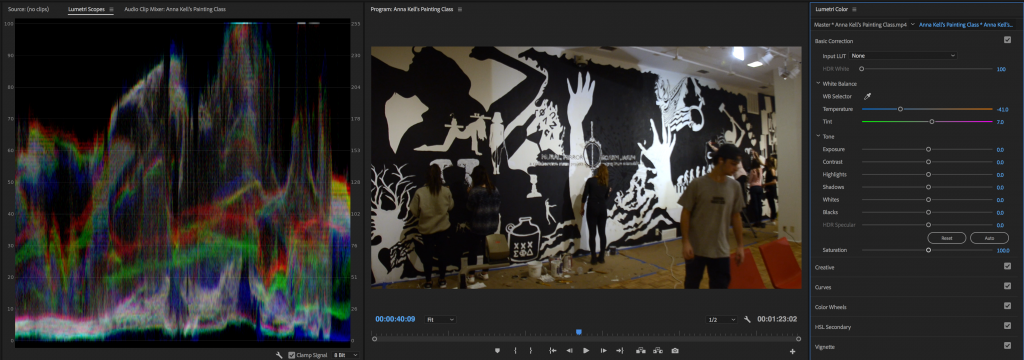

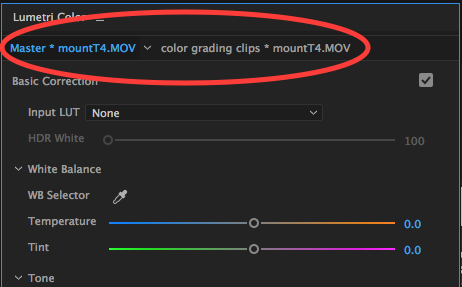

At the very top of the Lumetri Color panel, above the Basic Correction section, you should see two pieces of text: “Master,” followed by an asterisk and the name of the clip; and the name of your timeline sequence, followed by an asterisk and the name of your clip. By default, the text with the name of your sequence will be highlighted in blue – this is the normal color grading mode that we have been using thus far. Clicking on the text with the word Master will switch you to that mode. Clicking on the down arrow will show the timecode of every section of the clip that has been used.

As I mentioned, the master adjustment will affect every instance of that piece of media. This makes it useful for things like basic corrections – if you need to change the white balance setting for the entire take, this would be a good way to do it. The master adjustment and the regular adjustments are totally separate as well, so you can make some settings universal and then continue to refine the look of your film on a shot-by-shot basis.

I honestly don’t use the master adjustments very often. Since Lumetri defaults to the non-master setting every time you click on a clip, it’s easy to forget that the master mode is even there. On larger projects with lots of sub-clips, however, it can be a great way to save yourself some work.

Obsolete Effects

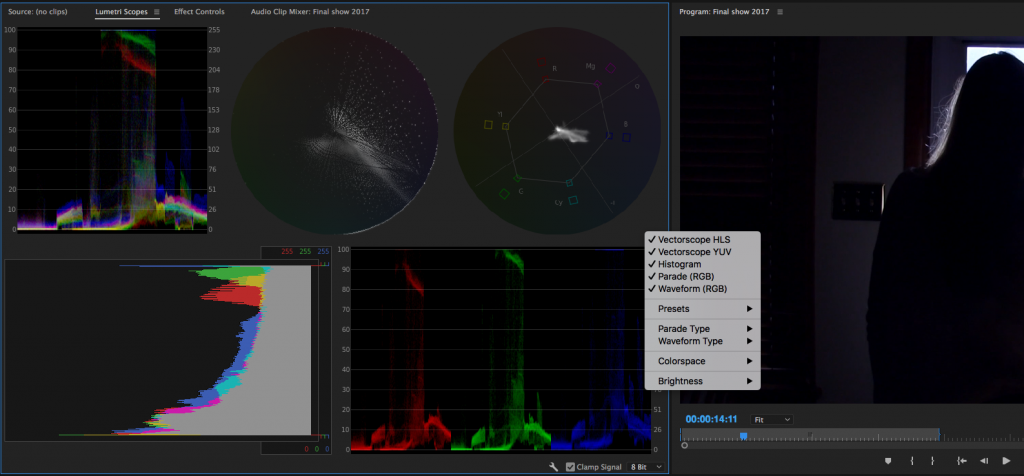

For the past several years, Adobe has continued to add more and more functionality to the Lumetri Color panel with each successive version of Premiere. This has allowed editors to handle more of the color grading process directly within the software they are already using, without moving their projects to a different application. One side effect of this is that Adobe has largely ignored their own dedicated color grading software – SpeedGrade – and made several of the older color grading effects within Premiere obsolete.

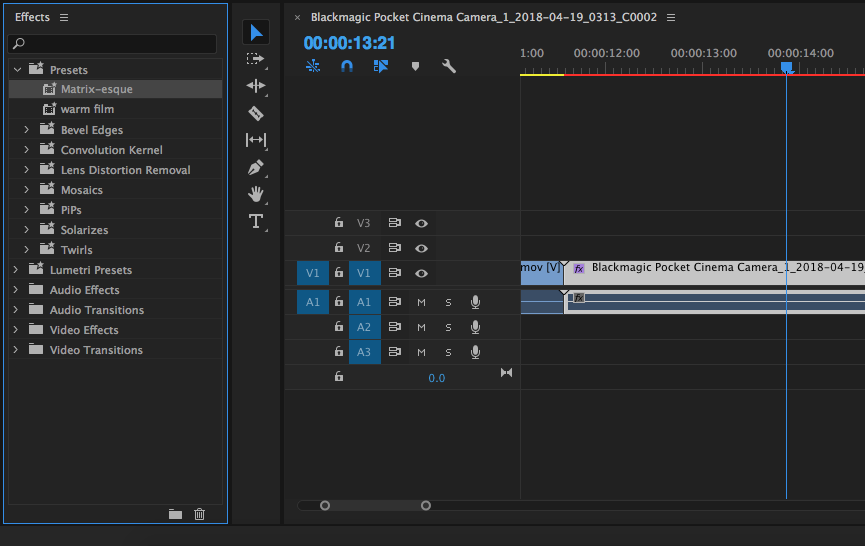

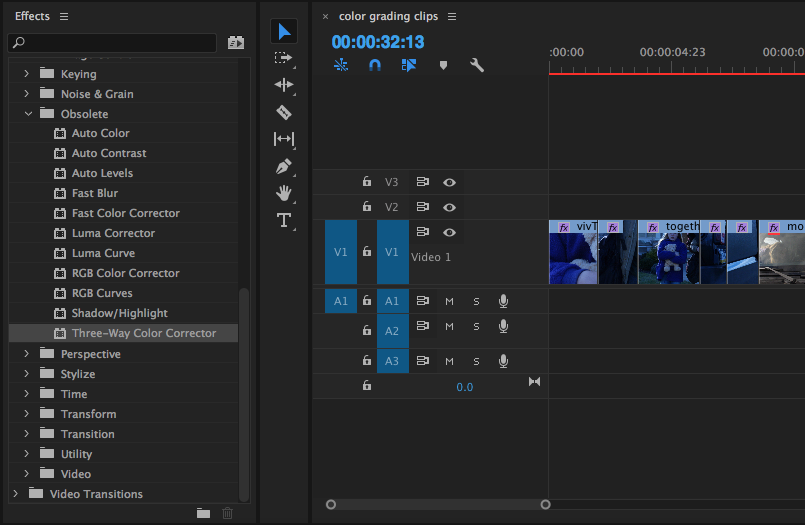

However, those effects are still available – they just no longer appear in the Color Correction category. If you open the Effects panel and scroll down through the video effects, you’ll find a folder appropriately named “Obsolete,” which is comprised almost entirely of color-related options.

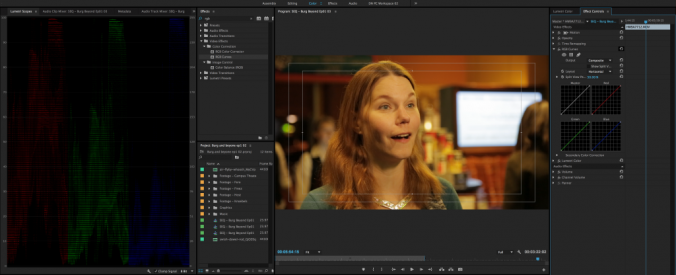

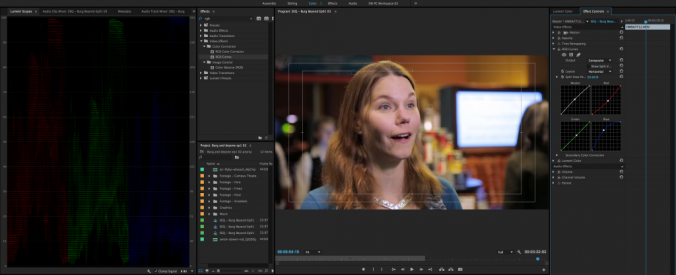

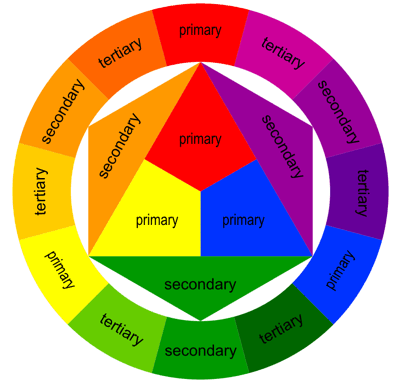

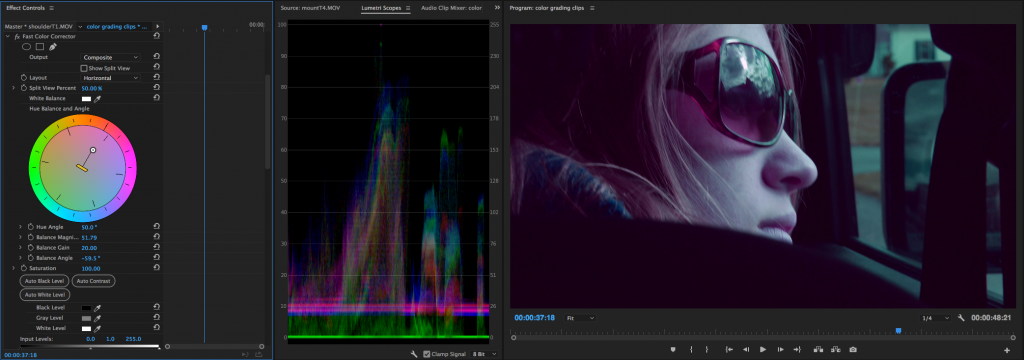

For a long time, I did all of my color correction and grading in Premiere using either the Three-Way Color Corrector, Fast Color Corrector, RGB Curves, or some combination thereof. These are still useful effects, but virtually all of their functionality has been replicated in Lumetri. The Fast Color Corrector is dominated by a large color wheel that can be used to alter the “hue balance and angle” of a shot. This can be a fun way to change the look of your footage. There are also lots of options related to luminance, so you can dial in the contrast, white levels, and black levels.

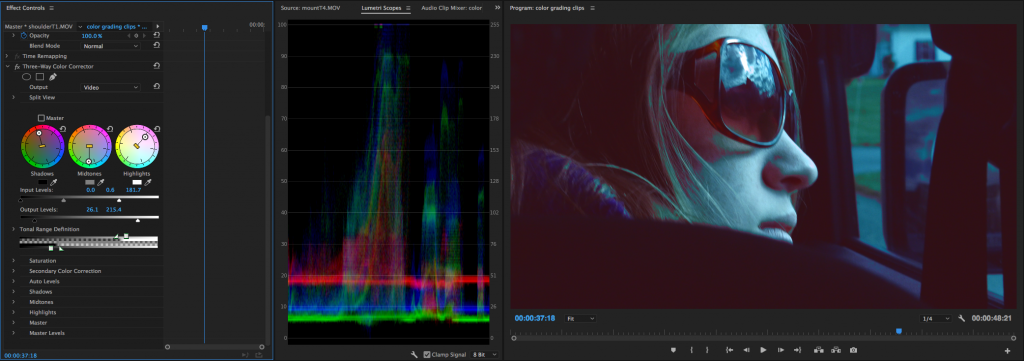

The Three-Way Color Corrector probably bears the closest resemblance to the Lumetri panel we now have. It has three color wheels, allowing you to adjust the shadows, midtones, and highlights separately. There are also sliders for saturation and luminance, as well as a “secondary” corrector for fine-tuning.

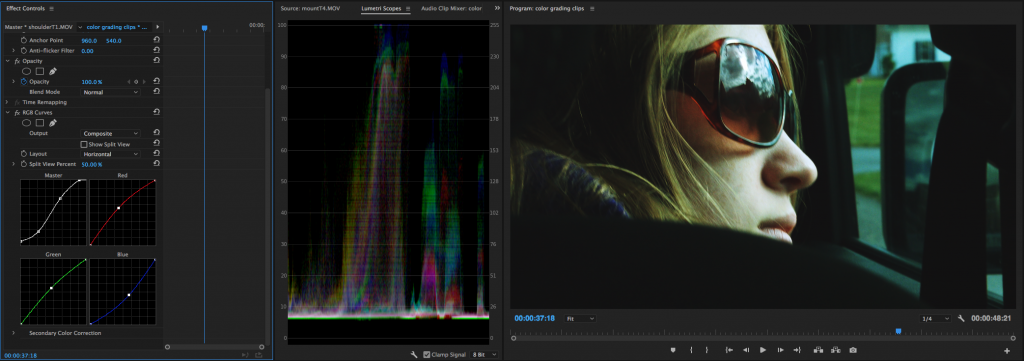

The RGB Curves effect is very simple, but that’s what I really like about it. It gives you separate graphs for luminance, red, green, and blue, which I actually prefer to the combined graph in Lumetri. Curves adjustments let you really play with the look of footage quickly – you can raise black levels, add contrast curves, and alter the overall color cast with just a few clicks.

Now that Lumetri Color has evolved into such a full-featured toolset, is it still worth using any of the obsolete effects? I actually think that it is. The “Hue Balance and Angle” wheel in Fast Color Corrector and Three-Way Color Corrector is a unique adjustment tool that can be fun to experiment with – and if you don’t need an entire suite of color grading options, the RGB Curves can be a simple way to make a quick adjustment. There are other simple effects in the obsolete folder as well, for things like highlight and shadow adjustments. Adding them as individual effects lets you customize not only what is applied, but the order in which they are applied.

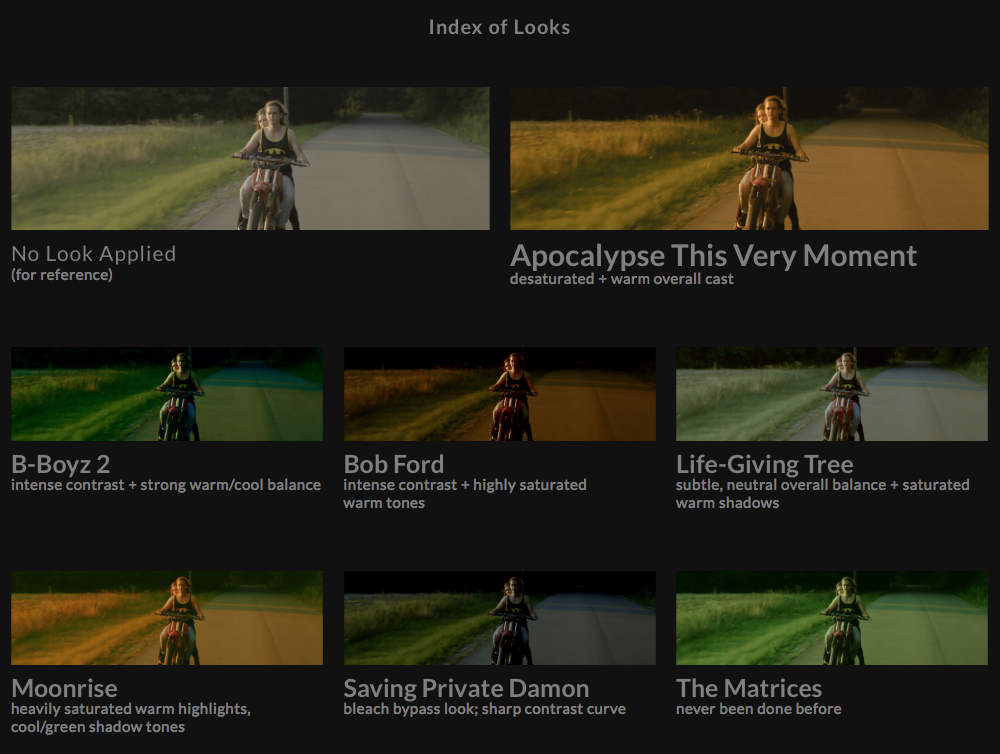

There’s always more to learn, but at this point you should have a good set of techniques to build upon. If you need some inspiration, check out some of the videos in the Blog Posts section. Experiment and have fun!